Why does quantum mechanics use complex numbers extensively? Why is the inner product of a Hilbert space antilinear in the first argument? Why are Hermitian operators important for representing observables? And what is the i in the Schrödinger equation doing? This post explores these questions through the framework of groupoid representation theory. While this post assumes basic familiarity with complex vector spaces and quantum notation, it does not require much pre-existing conceptual understanding of QM.

Roughly, there are two kinds of complex numbers in physics. One is a phasor: something that has a phase. The other is a scalar: a unitless number representing a combined scale factor and phase-translation. Scalars act on phasors by translating their phases. Generally speaking, scalars are better understood as elements of an algebraic structure (groups, monoids, rings, fields), while phasors are better understood as vectors or components of vectors. We will informally use the term “multi-phasor” for a collection of phasors, such as an element of .

An example of a phasor would be an ideal harmonic oscillator, which has a position given by . Its state is best thought of as also including its velocity

. Note that

has constant magnitude, corresponding to conservation of energy. Now over time, the normalized

point moves in a circle. Phase-translating the system would imply cyclical movement through phase space; a full cycle happens in time

. A complex scalar specifies both how to phase-translate a phasor, and how to scale it (here, scaling would apply to both position and velocity). By representing the phasor

as a complex number such as

, multiplying by a complex scalar will phase-translate and scale. Here, multiplying by i represents moving forward a quarter of one cycle, though in other representations, –i would do so instead. The phasor is inherently more symmetric than the scalar; which phase to consider “1” in this complex representation, and whether multiplication by i steps time forwards or backwards, are fairly arbitrary.

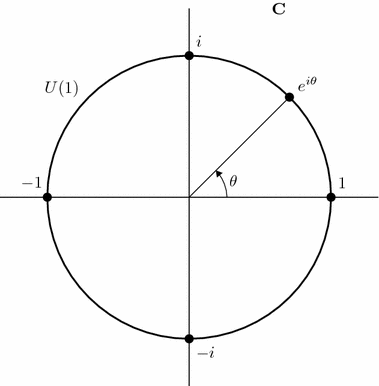

To understand complex scalars group-theoretically, let us denote by the non-zero complex numbers, considered as a group under multiplication. An element of the group can be thought of as a combined positive scaling and phase translation. Let

be the sub-group of

consisting of unitary complex numbers (those with absolute value 1); see also unitary group. Let

be the positive reals considered as a group under multiplication. Now the decomposition

holds: multiplication by a non-zero complex number combines scaling and phase translation.

First attempt:  -symmetric sets

-symmetric sets

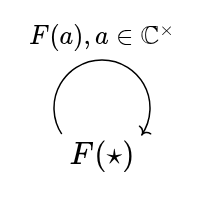

If G is a group, let BG be the delooping groupoid: a groupoid with a single object (), and one morphism per element of G. A convenient notation for the category of G-symmetric sets (and equivariant maps between them) is the functor category [BG, Set]. In this case,

.

A -symmetric set is a set S with a group action

(

) satisfying

and

. We now have a set of elements that can be scaled and phase-translated. Hence, S conceptually represents a set of phasors (or multi-phasors), which are acted on by complex scalars.

Let S, T be -symmetric sets. A map

is equivariant iff

for all

. This is looking a lot like linearity, though we do not have zero or addition. To handle additivity, it will help to factor out the

symmetry.

Second attempt: U(1)-symmetric real vector spaces

We will use real vector spaces to factor out the symmetry. While we could use

semimodules (to model negation as action by

), real vector spaces are mathematically nicer. Let

be the category of real vector spaces and linear maps between them.

To get at the idea of using real vector spaces to handle symmetry, we consider the functor category

. Each element is a real vector space with a U(1) action. We can write the action as

for complex unitary a. Note

is linear for fixed a.

Let U, V be real vector spaces with U(1) symmetry. A linear map is U(1)-equivariant iff

for all complex unitary a.

Now suppose we have opposite-phase cancellation: for

, which is valid for ideal harmonic oscillators, and of course relevant to destructive interference. We now extend S to a complex vector space, defining scalar multiplication as

for real a, b. This is a standard linear complex structure with the linear automorphism

. The assumption of opposite-phase cancellation is therefore the only distinction between a U(1)-symmetric real vector space in

and a proper complex vector space.

(an abstract representation of the double-slit experiment, depicting opposite-phase cancellation through representation of phasors as colors)

Third attempt: O(2)-symmetric real vector spaces

We see that is close to the category of complex vector spaces and linear maps between them. Note that

, where SO(2) is the set of rotations in Euclidean space. This of course relates to visualizing phase translation as rotation, and seeing phasors as moving in a circle. While SO(2) gives 2D rotational symmetries of a circle, it does not give all symmetries of a circle. That would be the orthogonal group O(2), which includes both rotation and mirroring. We could conceptualize mirroring as a quasi-scalar action: if action by i rotates a wheel counter-clockwise 90 degrees, then mirroring is like turning the wheel to its opposite side, so clockwise reverses with counter-clockwise.

To make the application to phase translation more direct, we will present O(2) using unitary complex numbers. The group has the following elements (closed under group operations): for complex unitary a, meant to represent a phase translation, and J, meant to represent a distinguished mirroring. We have the following algebraic identities:

Note that since a is unitary, the conjugate is an inverse. We can derive that

, so mirroring reverses the way phase translations go, as expected.

Now the category , noting the previous correspondence with complex vector spaces, motivates the following definition. A real structure on a complex vector space V is a function

that is an antilinear involution, i.e.:

for complex

For example, has a real structure

. So the involution

generalizes complex conjugate.

Now, if U and V are complex vector spaces with real structures , then a linear map

is σ-linear iff it satisfies

for all

. This condition accords with O(2)-equivariance.

While real structures are useful in quantum mechanics (notably in the theory of C* algebras), they are not well suited for quantum states themselves. Imposing a real structure on the state space, and a corresponding σ-linearity condition on state transitions, is too restrictive for Schrödinger time evolution.

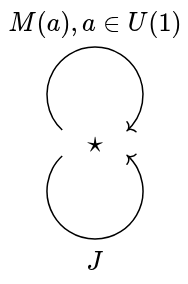

Fourth attempt: O(2) as a groupoid

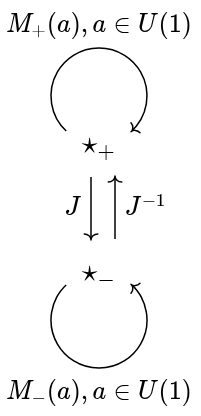

Since O(2) has two topologically connected components (mirrored and un-mirrored), it is perhaps reasonable to separate them out, like two copies of U(1) glued together. Conceptually, this allows conceiving of two phase-translatable spaces that mirror each other, rather than treating mirroring as an action within any phase-translatable space. We consider a “polar unitary groupoid” , which has two objects

. For complex unitary a, we have morphisms

and

, which compose and invert as usual for U(1). We also have an isomorphism

satisfying

.

relates to O(2) through a full and faithful functor (

). The only essential difference is in separating the two connected components of O(2) into separate objects of the groupoid

.

Now we can consider the functor category . An object of this category picks out two U(1)-symmetric real vector spaces (of which complex vector spaces are an important class), and provides a real-linear isomorphism between them corresponding to J; this isomorphism is not, in general, complex-linear. Importantly, the groupoidal identity

yields a corresponding fact that the two U(1)-symmetric real vector spaces have opposite phase-translation actions.

To simplify, we can achieve opposite phase-translation actions as follows. Let V be a complex vector space. Let be a complex vector space with the same elements as V and the same addition function. The only difference is that scalar multiplication is conjugated;

. We call

the complex conjugate space of V.

Improving the notation, if , we write

for the corresponding vector in the complex conjugate space. Note the following:

for complex

The choice of notation here is not entirely standard (although

is standard), but is convenient in that, for example,

looks like

, and they are in fact equal.

Let U and V be complex vector spaces. If , define

as

. This definition matches what we would expect from morphisms (natural transformations) in

. By treating f and

as separate functions, we avoid the rigidity of σ-linearity.

What we have finally derived is a simple idea (complex vector spaces and their conjugates), but with a different groupoid-theoretic understanding. Now we will relate this understanding to quantum mechanics.

The inner product

In bridging from complex vector spaces to the complex Hilbert spaces used in quantum mechanics, the first step is to add an inner product, forming a complex inner product space. Traditionally, the inner product is a function , where

is a Hilbert space (or other complex inner product space). While the inner product is linear in its second argument, it is notoriously anti-linear in its first argument. So while on the one hand

, on the other hand,

. Also, the inner product is conjugate symmetric:

.

The anti-linearity and conjugate symmetry properties are not initially intuitive. To directly motivate anti-linearity, let be a quantum state. Now the inner product

gives the square of the norm of the state

, as a non-negative real number. If the inner product were bilinear, then we would have

. But multiplying

by i is just supposed to change the phase, not change the squared norm. Due to antilinearity,

as expected.

Now, the notion of a complex conjugate space is directly relevant. We can take the norm as a bilinear map . The complex conjugate space

gracefully handles antilinearity:

. And we recover conjugate symmetry as

; the overlines make the conjugate symmetry more intuitive, as we can see parity of conjugation is preserved.

Using the universal property of the tensor product, we can equivalently see a bilinear map as a linear map

; for the inner product, this corresponding map is

. This correspondence motivates studying the complex vector space

.

Real structure on tensor products

The space has a real structure, by swapping:

. To check:

as desired. Of course, also has real structure, so we can consider σ-linear maps

. First we wish to check that the tensor-promoted inner product is σ-linear:

.

Noticing that the inner product is σ-linear of course raises the question of whether there are other interesting σ-linear maps . But we need to bridge to standard notation first.

Bra-kets and dual spaces

Traditionally, a ‘ket’ is notation for a vector in the Hilbert space H. A ‘bra’

is an element of the dual space of linear functionals of the form

; this dual space is called

. We convert between bras and kets as follows. Given a ket

, the corresponding bra is

, which linearly maps kets to complex numbers. The ket-to-bra mapping is invertible, and antilinear, due to Riesz representation.

In our alternative notation, we would like the dual to be linearly, not antilinearly, isomorphic with

. This is straightforward: given

, we take the partial application

. This mapping from

to

is a linear isomorphism when V is a Hilbert space:

(note the non-standard notation!). As such,

; the dual space is isomorphic to the complex conjugate space.

Tensoring operators

We would now like to understand linear operators, which are linear maps . Because

, we can see the operator as a linear map

, or expanded out,

. Tensoring up, this is equivalently a linear map

. Of course, this is related to the standard operator notation

; we can see the operator as a quadratic form in a bra and a ket.

More explicitly, if is linear, the corresponding tensored map is

. We would like to understand real structure on linear operators through real structure on tensored maps of this type. If

is linear, we define the real structure

. As a quick check:

.

We can apply this real structure to :

.

By definition, the Hermitian adjoint satisfies

; note

. As such,

Therefore, . This justifies the Hermitian adjoint as the canonical real structure on the linear operator space

, as is standard in operator algebra.

Now we can ask: When is σ-linear?

Assuming is a Hilbert space, this holds for all

iff

, i.e. A is Hermitian. This is significant, because Hermitians are often used to represent observables (such as in POVMs). It turns out that, among linear maps

, the Hermitians are exactly those whose corresponding tensored maps

are σ-linear.

Let a member of a complex vector space with a real structure σ be called self-adjoint iff

. As an important implication of the above, if

is Hermitian, then

maps self-adjoint tensors (such as those corresponding with density matrices) to self-adjoint complex numbers (i.e. real numbers). This is, of course, helpful for calculating probabilities, as probabilities are real numbers.

Unitary evolution and time reversal

While Hermitian operators are those for which , unitary operators are those for which

. We will consider time evolution as a family of unitary operators

for real t, which is group homomorphic as a family (

).

A simple, classical example of unitary evolution is that of a phasor representation of a simple harmonic oscillator, (for real a). The unitary evolution is given by

, a multiplicative factor on the phasor to advance it in time. By convention, we have decided that time evolves in the +i direction (multiplicatively), assuming

. We can find this direction explicitly by differentiating:

.

With classical phasors, it is easy to see what physical quantities the representation corresponds to; here, the imaginary part of the phasor represents the position multiplied by the frequency . Interpreting quantum phasors is less straightforward. We can still take the derivative

, which approximates

as

as

. We recover

through the matrix exponential

, which generalizes

in the single-phasor case.

Because the family is unitary, we have

for Hermitian H; note

is Hermitian iff H is. In the specific case of the Schrödinger equation,

where

is the Hamiltonian, and

is the reduced Planck constant (a positive real number). The direction of the action of i in quantum state space is meaningful through the Schrödinger convention

(as opposed to

).

Complex conjugate therefore relates to time reversal, though is not identical with it. , while

. In the real structure on linear operator space

given by

, a Hermitian is self-adjoint, like a real number in

, while

is skew-adjoint (

), like an imaginary number in

(i.e.

for real b).

To bridge to standard time reversal in physics, complex conjugates relate to time reversal operators in that a time reversal operator (satisfying

) is anti-linear, due to the relationship between time and phase. In the simpler case,

, though in systems with half-integer spin,

; see Kramers’ theorem for details. In the latter case, time reversal yields a quaternionic structure on Hilbert space (rather than a real structure). In relativistic quantum field theory, one may alternatively consider the combined CPT operation, which includes time reversal but typically squares to the identity. Like time reversal, CPT is anti-linear; either C or P on its own would be linear, so the anti-linearity of CPT necessarily comes from time reversal.

Complex conjugation is not itself time reversal, but any symmetry that reverses time must conjugate the complex structure; CPT is the physically meaningful anti-linear involution that accomplishes this. The sign applied to i in the Schrödinger equation is not an additional law of nature, but a choice of orientation. Nature respects the equivalence of both choices, while observables live in the self-adjoint subspace where the distinction disappears.

Conclusion

Groupoid representation theory helps to understand Hilbert spaces and their relation to operator algebras. It raises the simple question, “if action by a unitary complex number is like rotating a circle, what is like mirroring the circle?”. This question can be answered precisely with a real structure, and less precisely with a conjugate vector space. The conjugate vector space helps recover a real structure, through the swap on the tensor product , which relates to the inner product and the Hermitian adjoint

.

While on the one hand, complex conjugation is a simple algebraic isomorphism (if i is a valid imaginary unit, then so is –i), on the other hand it has a deep relationship with physics. The Schrödinger equation relates i to a direction of time evolution; complex conjugation goes along with time reversal. The Hermitian adjoint, as a real structure on linear operator space, generalizes complex conjugate; it keeps Hermitians (such as observables and density matrices) the same, while reversing unitary time evolution.

Much of the apparent mathematical complexity of quantum mechanics clicks when viewed through representation theory. Algebra, not just empirical reality, constrains the theoretical framework. Geometric representations of physical algebras serve both as shared intuition pumps and as connections with the (approximately) classical phenomenal space in which empirical measurements appear. Understanding the complex conjugate through representation theory is not advanced theoretical physics, but it is, I hope, illustrative and educational.